The Wideners, the Titanic, and Lynnewood Hall

Lynnewood Hall, Philadelphia

Sheltering Angel, my Titanic story, introduces a cast of people who actually endured or succumbed to the tragedy of April 15, 1912. Among the multimillionaires aboard the ill-fated ship’s maiden voyage were George Widener, his wife Eleanor, and their 27-year-old son Harry. One might consider the Wideners fortunate because of their extreme wealth, but a closer look reveals that an excessive lifestyle doesn’t necessarily equate with good fortune.

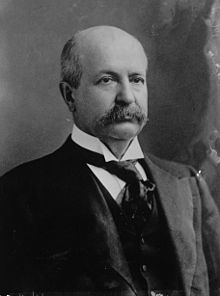

Peter Arrell Brown Widener

Born in Philadelphia in 1861, George was the firstborn son of Hannah Dunton and Peter Arrell Brown Widener. The elder Widener amassed staggering wealth in the steel and tobacco industries and was at one point estimated to be worth $25 billion.

What did one do with all that cash before 1909 when the U.S. Congress enacted the 16th Amendment initiating a tax on income? As with the robber barons of Newport, Rhode Island, they built castle-sized houses. For industrialist Peter Widener, who had come from very little, it was important to make a statement about the wealth he had acquired. At a cost of nearly $8 million ($293 million inflated for 2023), he contracted with architect Horace Trumbauer to design and oversee the construction of a 110-room mansion. In part, Widener wanted the manor to showcase his private art collection that rivaled the finest galleries in the world, including works of European masters like Vermeer and Rembrandt.

Called “the American Versailles,” Lynnewood Hall, as Widener named it, was at the time the largest private dwelling not only in Philadelphia but in all of America. The mansion took nearly three years to build between 1897 and 1900. In 1896 when Hannah died in a tragic yachting accident off the coast of Maine, the 400 acres of Philadelphia land had been purchased and plans were moving ahead to build the estate. Widener decided to move forward without his beloved wife. Eventually his son George would inherit Lynnewood, so it seemed logical to leave an architectural legacy.

Peter had the walls of Lynnewood Hall lined with 70,000 square feet of limestone. The residence boasted 55 private bedrooms, 20 full bathrooms, and a number of grand rooms for hosting parties and receptions, including a ballroom that accommodated a thousand guests. Other rooms he dedicated solely to his art collection. The estate required 37 full-time, permanent staff members to tend the indoors and 60 groundskeepers for the exterior, including sculpted gardens designed by a famous French landscape architect.

Two renowned interior designers planned each room, and guests entered either through a set of doors covered in bronze or another of gold. Widener wanted every detail to reflect his love for the finest things life had to offer.

More than 300 priceless pieces adorned the walls and open space, from porcelain sculptures to expensive furniture carved for royalty and stained glass windows by Giovanni di Domenico. Including a large indoor swimming pool, the estate required so much water that it had its own reservoir.

In 1900, aging at 66 years old, Peter moved into Lynnewood Hall as soon as construction was completed. When George Widener came of age, he joined his father’s business and eventually took over running of the Philadelphia Traction Company, overseeing the development of cable and electric streetcar operations and serving on the board of several area businesses. A patron of the arts like his father, George became a director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. When it came to romance, Eleanor Elkins, socialite, heiress, and daughter of his father’s business partner, not only was an attractive prospect for marriage, but she was convenient as well. Their marriage bore them two sons and a daughter.

George Dunton Widene

Eleanor Elkins Widener

Fascinating history of America’s super wealthy.

Thanks for your comment, JL.

Lynnewood Hall stands a chance only if the materials needed for the restoration come from Europe. One of the rooms with wooden panelling, some time ago had a brown/rusty colour marble mantle piece installed from a brocante. Some materials were installed by CBRE,so that certain elements would not be stolen. Wooden panelling has been sourced from England and France. The bulk of the materials are in storage.

Thanks for your comment, Tracy. I do hope the landmark can be saved. ~Louella